Ĭoncentration of income is enabled by and perpetuates a concentration of wealth – the accumulation of financial and productive capital. įigure 1: Composition of income earned by the Top 1% income earners. About 60% of capital income flows in recent years have been siphoned to this income class. This class also monopolizes the lion’s share of capital earnings in the US. The earnings of the rich derive in large part not from “working” but through ownership of assets. Thus the share of capital income – income from ownership of financial and productive assets – rises steeply from 30% to over 60% in the top 1% of the income distribution. The share of entrepreneurial income (profits from ownership or partnerships in enterprises) for this class varied from 20-32%, constituting another big chunk of its earnings. The top 1% draws a lion’s share of its earnings from ownership of financial assets. The data for 2007 reveal that the share of capital income (rentier income including dividends and interest from ownership of financial claims) for this group increases from around 10% to 33% of total income, as we go up the income ladder within this group, while the share of salary income slides from 69% to 38%.

Figure 1 shows the composition of income as we go up the distribution within this group (the top 1%).

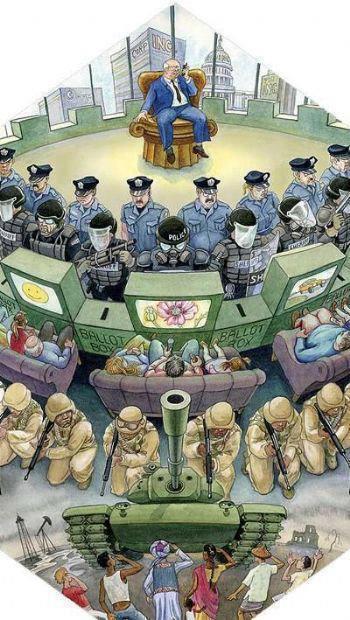

A big chunk of the income earned by the top 1% of the income distribution in the US is earnings from financial capital – ownership of stocks, bonds and other financial assets. The enrichment of the top 1%, however, is not simply through this skewed wage growth. The compensation paid to the average CEO increased from 40 times that paid to the average worker in 1980, to nearly 300 times in 2000, before declining slightly to 240 times in 2008. While wages for the average worker have remained relatively stagnant compensation paid the upper end of the corporate hierarchy has grown over the past decades. At the same time a new managerial revolution has reinforced the alliance between the executive-managerial class and financial and corporate capital. This “coup” fuelled the enrichment of the top elite at the expense of the working class. The neoliberal backlash, in the wake of the stagflationary crisis of the seventies, ushered in a period of the consolidation of the power of financial and corporate capital in the US alongside a concerted attack on labor. About 24% of the national income of USA flows into the hands of the top one percent of American households. The growing inequality of income since the eighties is well documented. They reflect the stark reality of the structure of the US economic and political landscape – the growing concentration of power in the hands of an elite coterie and the widening chasm that separates this elite from the rest of the American people. Absurd or outrageous as these developments might be, they are not inexplicable.

Even more outrageous, is the unfolding farce of a potential budget crisis (which was definitely not eased by the tax breaks to the rich!) being cynically deployed to launch an aggressive assault not just on the earnings and benefits enjoyed by state employees (including teachers) but also on the hard worn rights of collectively bargaining across the country. An observer of US politics would be struck by the absurdity of the US Congress scuttling a proposal to let the Bush tax breaks expire for households with incomes over $250,000, as part of the deal for letting unemployment insurance be extended, at a time when most American people are still struggling with the disastrous impact of the most profound economic crisis since the Great Depression.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)